Environmental historian Daniel Haines is Associate Professor, History of Risk and Disaster, University College London. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, he discussed the Indus River:Can you tell us about the role the Indus played in consolidating colonial power?Soon after British colonialists annexed Sindh and Punjab in the mid-19th century, they began constructing large canal colonies which drew water from the Indus and its tributaries like the Sutlej. The British Raj used these canal colonies to transform agriculture in the Indus Basin with the one aim of introducing more cash crops — they wanted to raise more money through agricultural taxes for the imperial government.

They also wanted to give opportunities to some groups they thought could be loyal, such as retired soldiers who were often given land grants in Punjab. This was part of a colonial project of ‘modernising’ sections of Indian agricultural society in the 19th and 20th centuries.

As the freedom movement grew and the colonialists faced pressure from nationalists, they began projecting the idea of ‘development’ to boost imperial legitimacy — their argument was that although they were a foreign power, they had brought progress to Indians. The Indus became an intrinsic part of that argument.

What is the postcolonial story of the Indus?After Independence, India still had a largely agricultural economic base. Its industries were growing but farming was key in the early years — irrigated agriculture was very important for Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh. However, Partition had left the majority of developed irrigated lands in what became ‘

Pakistan’.

India also had many refugees to resettle, some from those agricultural lands. The government there-fore had to intensively develop irrigation on the rivers moving through the north. For Pakistan, the Indus was an even more important part of its national economy. India is huge and has many major river basins. In contrast, for Pakistan, the Indus and its tributaries are the only major source of river water. From Pakistan’s perspective, continuing to get water from this was essential for agriculture.

What role did the World Bank play in shaping 1960’s Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) — and why the US-driven Bank, after a British colonial history?In the late 1940s-early 1950s, the World Bank was a new institution, seeking a role in the international system and figuring out how to use its expertise and finances. It got pulled between India and Pakistan at the suggestion of David Lilienthal, a senior American bureau-crat. He visited India and Pakistan in 1951 and then wrote, calling on the US government and the World Bank to take a lead role in mediating the Indus water dispute.

This was basically in service of Western geopolitical aims, it was an attempt to try to reconcile India and Pakistan, so they’d join the US coalition against the then-Soviet Union in the Cold War.

That wasn’t a very realistic expectation but the World Bank wrote to both governments which agreed to join talks. In theory, the World Bank was only supposed to facilitate negotia-tions — in practice, its officials proposed their own plans at times. The Bank wasn’t very closely aligned to American strategic interests in this particular case though. The US state department tried to keep out of negotiations till the late 1950s. Then, they came on board as a funder to grants in the Indus Basin Development Plan, mainly support-ing new works in Paki-stan. I believe the Bank didn’t favour any one side though.

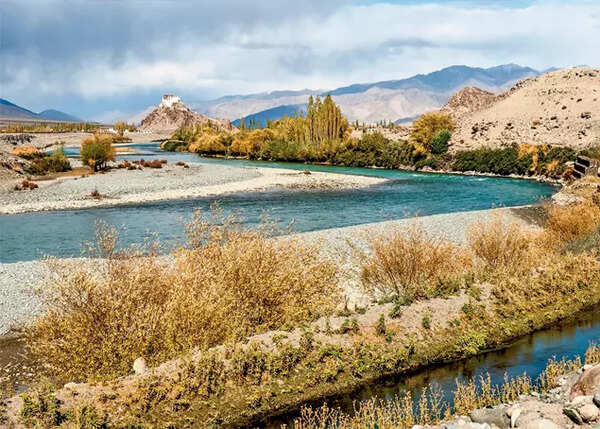

What is the ecological backdrop to the Indus?Interestingly, China and Afghanistan are also riparians in the Indus system. The Indus rises in Tibet in China and the Kabul River joins this from Afghanistan. The volume of water going through these regions is much less though than the flows moving through India and Pakistan.

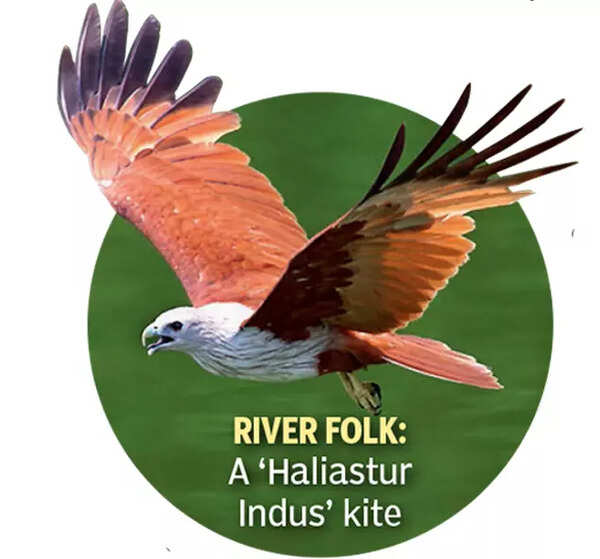

The river itself has manifold ecosystems, from the high Himalayas to the marshy Indus delta in southern Pakistan, all completely dif-ferent landscapes and diverse ecologies. Hun-dreds of millions of people live in the Indus Basin itself but the number of lives this river affects is much greater — farmers in Punjab and Haryana, for instance, grow crops which feed into the national economy, people outside the Indus process and export these crops, etc.

How is climate change impacting the Indus now?The Indus system is highly environmentally precarious. The river delta in southern Sindh in Pakistan, for instance, has seen a very serious reduction in water flows since the British began irrigation development there. The active area of the delta has shrunk by a huge propor-tion with both political and ecological impacts, we now see mangroves along the coast of Pakistan vanishing, which makes that country much more vulnerable to storm surges. Simi-larly, the eastern waters bear impacts, the Ravi, which flows around Lahore, was assigned to India under the IWT. Its water is mostly used upstream in India for farming.

Very little goes to Pakistan and under the legal framework, this is completely legitimate, India has no obliga-tion to let this water out. Hence, Lahore is now experiencing reduced water flows, which has serious health implications since the city’s sew-age effluents aren’t being efficiently carried out.

Alongside, glacial mass in the Himalayas is shrinking as global warming increases, over the next few decades, as the glaciers melt, there will likely be severe floods, followed by a sharp lack of water. We will see a very complicated picture emerg-ing of anthropogenic im-pacts affecting communities dependent on Indus ecosystems.

Are there other instances of water playing a key role in international relations?The Nile Basin has seen historical tensions rising between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan at times, this also dates back to British colonialism. There was good coop-eration over the Mekong River which is shared between several Southeast Asian nations. The Danube flows through many countries in Europe, however, those nations are not dependent on river-fed agri-culture. The problem there is about navi-gation rights rather than sharing water.

Views expressed are personal